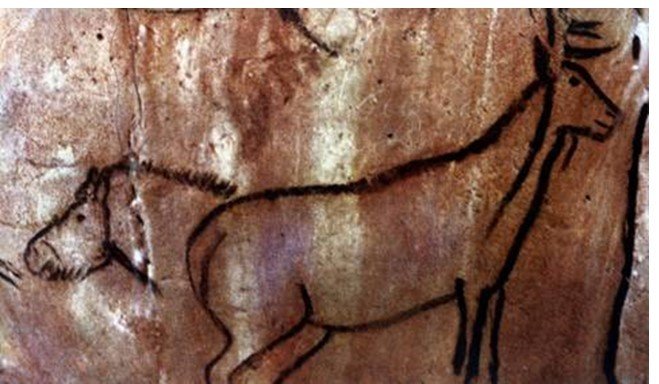

I asked the students if they thought it was beautiful. They did. And I asked them to describe what they saw. Students observed how the line is strong, thick and dark; how it delineated the contour of the animal’s back yet is so delicate as it comes down around the deer’s tail. The precision of the line is powerful and also sensitive as it moves around the contour of the animal. It is never mechanical. It goes over soft flesh and hard bones—goes in and out, moves up and down, gets thick and thin, breaks off and continues, all to show what that prehistoric deer was.

We saw that opposites are throughout this drawing. The antlers have grace and power. They are a oneness of gentle curve and sharp point. The heavy body of the deer is supported upon slender, delicate legs. The thick strong line of the back is gracefully contoured. A graceful, sweeping diagonal joins deer and horse. The line itself is both soft and firm.

I asked: “Is this drawing a beautiful oneness of strength and delicacy, power and exactness?” The class agreed: It is! It’s not delicate for two inches and strong for the next two inches. I told my students that these prehistoric paintings were beautiful for the same reason art of any age is beautiful. “All beauty,” Eli Siegel is the critic who explained, “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” And art, I learned, is the greatest opponent to contempt because an artist wants to see meaning in the things of the world and to express them with form and respect.

Seeing how strength and delicacy, power and precision were one in this cave painting affected my students very much, including several young men, who liked showing how tough they were. They thought being sensitive made them weak and vulnerable. Students long to be both strong and graceful, and they suffer because they feel they can’t be. This is a question teachers have too. We feel we have to be strong and then feel awful because we don’t feel we’re kind. I was once asked in an Aesthetic Realism consultation: “Do you have a ‘gentle’ attitude and a ‘fist’ attitude? Have you been unkind in both ways?” I had been! And I learned that in every instance of successful art, opposites are working well together.

I asked my students “Would it have been possible for early stone-age artists to paint these animals with that oneness of grace and strength, power and delicacy, 1) if they didn’t have these possibilities in themselves; and 2) if they didn’t observe these qualities in the animals?” The answer was a resounding, “NO!”

Students who can feel painfully separate from the people they see every day were moved to think about the feelings of a person who lived 35,000 years ago. As they saw they were related through the opposites to people so far back in time, what was far away and strange came to have immediate meaning for their lives.

They came to have a great care for these paintings and have a great respect for the mind of early man who painted them. And they began to think about the people they knew in a deeper, kinder way, including each other.

“When you think about how long ago these paintings were done,” wrote Grisel, “and how they were trying to make sense of what they saw in the world, this gives me a feeling of closeness to people.” And Tyshona was excited to see that “People thousands and thousands of years before me were trying to fulfill the same things I am.”

The ancient artist—like the modern artist and like us—was trying to put opposites together. What an artist long ago did beautifully in these cave paintings we now can learn from. The Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method has enabled my students and me—through the meaning and technique of art—to have large emotions about beauty, and to have a new respect for the world and for all people, of the past and now.

This article appeared in ArtBeat, the magazine of the Art Educators of New Jersey,

Volume 2, Fall 2010, p. 4-5