Rafael Tufiño: The Oneness of Intensity and Calm that We Want!

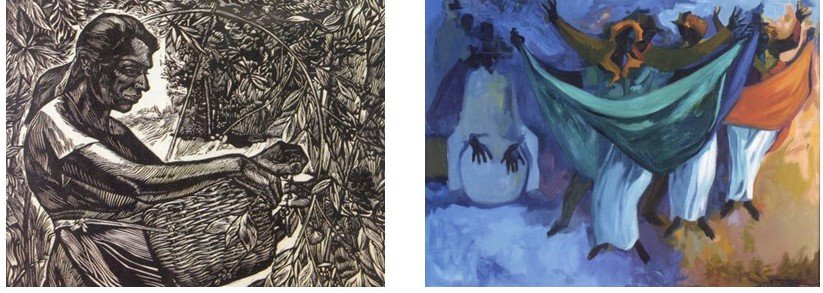

Rafael Tufiño, 1922-1980, has been described as embodying the “heart” of Puerto Rico. His feelings about its land and people are in his prints and paintings of harvesting coffee, peeling coconuts, dancing the bomba. In her essay on the artist, Dr. Teresa Tió writes that he created “images full of rhythm and human intensity” that also have “internal order and structure.”

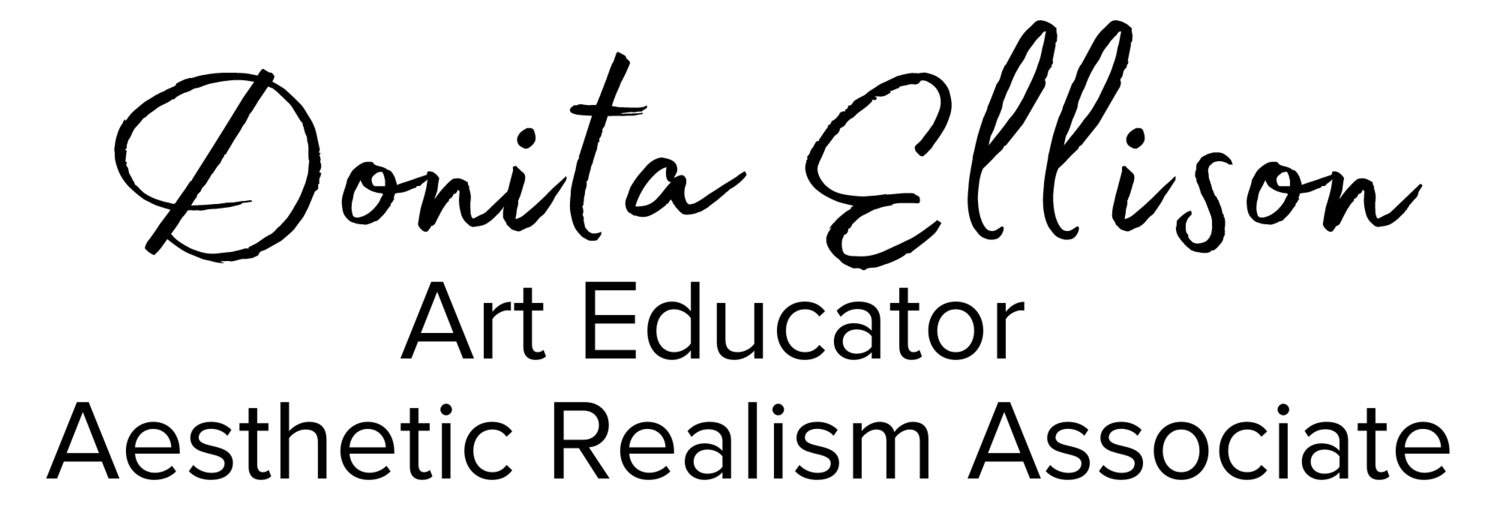

Tufiño, Raphael: Portafolio El caƒé, 1954 (recogedora de café con almud), linocut, image size 14-1/8”x 17-1/4.” Baile de bomba, 1969, oil on canvas, 29” x 40.”

How do we relate our desire for excitement and stir to our desire to take it easy and rest? I was troubled, as people are, by how I could be lazy and then have bursts of energy. In his landmark work of 1955, “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, Eli Siegel, the 20th century critic and educator who founded the philosophy Aesthetic Realism, asks:

“…can both repose and energy be seen in a painting's line and color, plane and volume, surface and depth, detail and composition?—and is the true effect of a good painting on the spectator one that makes at once for repose and energy, calmness and intensity, serenity and stir?

Tufiño’s 1951 linocut, Sugarcane Cutter –Cortador de caña- has a beautiful relation of intensity and calm, serenity and stir that we can learn from, as he depicts the rhythms of earth and the activity of work.

Tufiño, Rafael, Cortado de caña, 951, linocut print, image size 11 1/2 x 8 1/2 in, El Museo del Barrio, NY