Does Art Answer the Questions of Our Lives? — The Work of Hokusai Says Yes!

“The world is looking to have more meaning given to it, and more form, too. Art as energy does this.” —Eli Siegel

In one of his great essays on art, “Art as Energy,” Eli Siegel writes “The world is looking to have more meaning given to it, and more form, too. Art as energy does this.” That energy can be seen in the work of Katsushika Hokusai, (1760-1849) the 19th century Japanese painter and printmaker who once called himself “the old man mad about painting.”

In 1856 a large thing occurred in art history when prints by Hokusai and other Japanese printmakers arrived in Paris from Japan as packing in a shipment of porcelain. By chance these prints—with their vitality of color, bold flat shapes, dynamic compositions, and precision of line, texture and pattern—were seen by a young French artist, whose friends we know as The Impressionists. “These Japanese artists,” said Edgar Degas, “show us a new world.” The impact of these prints can be seen in the work of Monet, Cassatt, Van Gogh, to name just a few.

Monet, Claude, La Japonaise Cassatt, Mary, The Letter Van Gogh, Vincent, The Bridge in the Rain

And 150 years later Hokusai is a means for us to learn how our perception about the world can have energy, even exuberance at one with accuracy and form.

The Message of Art: A Thing Is Its Relation

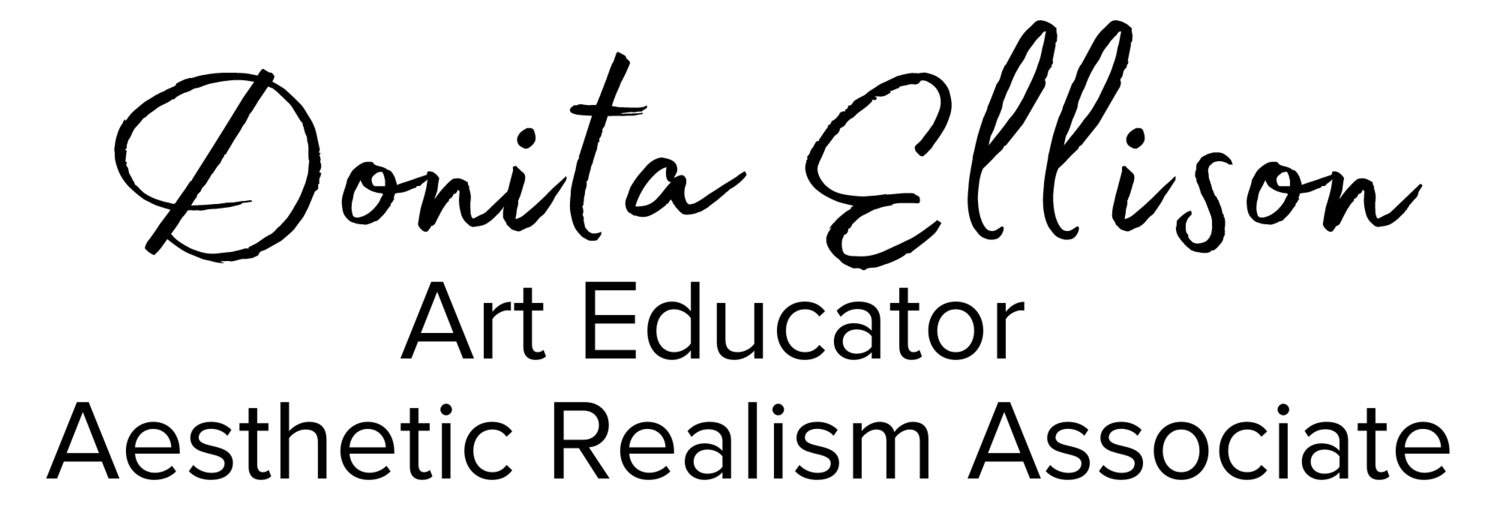

A most noted series of woodblock prints by Hokusai is his 36 Views of Mount Fuji. In the book Japanese Art Stefano Vecchia calls it “one of the world’s artistic masterpieces.” Each print, determined by the size of the woodblock is a mere 10 x 15 inches. In this small space Hokusai depicts the sacred mountain, Fuji-yama, home of the gods from almost every possible point of observation. He wants to know Mt. Fuji, see it in all its variety and moods and see all that it is related to.

Hokusai sees how Mt. Fuji is changed by weather: winter snow; spring cherry blossoms; the wind; and a thunderstorm raging below its summit. He looks at Mount Fuji in different lights: at dawn and dusk.

Hokusai, Katsushika, scenes from 36 Views of Mount Fuji

He sees it from city streets and the wilds of nature.

And in relation to the activities of people, as they gather clams, stack lumber, and even admire Mt. Fuji itself.

Whether up close or far away the artist does not get tired of seeing Mt. Fuji with more and more meaning. “Artistic energy” said Mr. Siegel “looks within, widens into relation, arranges, gives accuracy, or repose.” This is what we see in Hokusai’s carefully arranged compositions that, in view after view, lead our eye from a wide active, various world to the mountain, and captures the particularity, very essence of Mt Fuji.

What is Attention in Art and Life?

About the 36 views of Mt. Fuji, the critic Henri Focillon stated, “Japanese art never knew a more sustained contemplation of a theme.” [Hokusai 1914] Hokusai does not tire of giving his attention. And “how much attention one can give”, explains Eli Siegel, “is a problem of energy.”

How much attention I could give was a problem I had growing up in Springfield, Missouri. Much of the time I had a self-centered way of seeing, meaning I wanted the attention on me. My parents had active lives—my father bred and raced thoroughbred horses and my mother was a nurse—yet I felt they existed to cater to me. If I had a school activity, I expected Mom or Dad to drop their plans in order to chauffer me, and I often resented their relation to other things. For example, when they went square dancing on Saturday nights, I would call the dance hall, peevishly asking when they were coming home.

Even though I took piano lessons and later in college began to study art and sculpture, more and more I couldn’t give my attention to anything in a sustained way. This included reading a book, or keeping my eye on the object in a drawing class. In conversations my thought would wander back to myself, and my ideal of love was a man making me the center of his life. No wonder every relationship ended in anger and disappointment. I had no idea that the way I saw the whole world had anything to do with the lethargy and emptiness that I felt most of the time.

What enabled me to change was the kind and critical questions I heard in Aesthetic Realism consultations where I began to learn about the fight in every person between respect and contempt. In an early consultation I was asked:

Consultants Do you think you have a fight between being enthusiastic and not being interested,

having a lack of intensity about things?

Donita Ellison Yes

Consultants Is there a pretty deep and constant battle going on between you wanting to see value

coming from outside yourself and wanting to have all the value coming from yourself?

There was! And I learned that the more value I gave to things outside of myself, the more energetic and keener I would be!

This occurred as I have taught art for many years using the Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method. Students, too, have the fight between enthusiasm and dullness, and when they see that a work of art puts opposites together, the same opposites they are trying to make sense of, two things happen—they become more alive and also more composed.

I also learned that the purpose of love is to like the world through another person deeply and energetically. I fell in love with Jaime Torres, originally from Puerto Rico; he had an enthusiasm, an intensity about things, also humor that swept me—it countered my desire to feel stuck and inert. Jaime is a podiatrist, and he’s spoken passionately in Congress and on television on behalf of having health care in this nation based on the ethics he’s learned from Aesthetic Realism. And in classes with Ellen Reiss, I continue to learn how to see Jaime with more meaning and accurate, energetic perception. “Do you have the question,” Ms. Reiss asked me in one class, “of who is Jaime Torres?” I am glad to that say I do, and Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mt. Fuji encourages me to see that to know Jaime is to be interested in all his aspects and all he is related to.

The Artist Wants Things to Mean More!

In his essay Eli Siegel asks: “Is energy given to things, or do things have it? The upshot of art history is that it takes energy to find energy.” That is what impelled Hokusai. He wanted to see the energy within a thing, and for that thing to mean more to him. Born in 1760 he traveled across Japan with little more than brush and paper exploring and recording every element of nature and the human figure in its variety of movement. At the age of 75 he said:

“I have drawn things since I was six. All that I have made before the age of sixty-five is not worth counting. At seventy-three I began to understand the true construction of animals, plants, trees, birds, fishes, and insects. At ninety I will enter into the secret of things. At a hundred I shall certainly have reached a magnificent level; and when I am a hundred and ten, everything—every dot, every dash—will live.”

In his 89 years of life, he left the world over 10,000 woodcut prints, and 30,000 to 40,000 drawings.

One of the most recognizable images in world art, along with DaVinci’s Mona Lisa and Van Gogh’s Starry Night, is Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa, commonly known as The Great Wave. I believe the reason it remains today one of the most loved and reproduced works of art the world over is because of the way it puts together force and accuracy, great freedom and great precision. Every person wants to feel swept by the meaning of things and also feel orderly, in control. This is what The Great Wave does. It has an energy Mr. Siegel describes as “neat frenzy,” “the wild as shapely.”

Hokusai, Katsushika, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 1831, color woodblock, 10.1 x 14.9 inches

We see a mighty tsunami rising up from a tumultuous sea. As it crests upward and over, its massive curve rolling forward, it breaks into many spiky fingerlets of water, then into drops of foamy spray. Hokusai’s dots and dashes do live as they precisely define the power and delicacy of the wave. His technique is masterful. With economy of color—dark, middle, light blues, white, yellow and tan; and simplicity of line he looks within the wave, sees it as an exuberant force and graceful curve. In its rhythmic rise and fall it has terror and caress.

In the foreground are three yellow boats with pointed bows. One is carried upon the wave, another plunges through the wall of water, as the other at left is about to be engulfed. And even as the fishermen are in peril of the sea’s fury, Hokusai so exactly depicts the form of each head as they maneuver their oars in unison.

Everything in the composition is so carefully arranged to bring our eye to the actual subject—Mt Fuji—rising calmly and reposefully in the distance. The great wave seems to bow its frenzied crest to the mountain as its white foam appears to become snow falling upon the white capped peak of Fuji. Look at how the triangular form of the smaller wave in the foreground, is like that of the distant mountain, moving our eye from near to far, from the tumultuous waves to the reposeful mountain, whose delicate peak lovingly meets all time and space.

In “Art as Energy,” Eli Siegel explains:

“The artist says, I must see what this is; a person not as artist says, I must use this or protect myself from this. The energy that insists on a thing’s having more meaning is deeply the true kind.”

Hokusai’s energy of insisting on things having more meaning is the good sense every person hopes to have. The Great Wave shows we will be more ourselves not less, being vigorously attentive to reality in its many forms, including the reality of people.

—For Further Reading—

More about Hokusai KatsushikaHokusai.org

Works by Eli Siegel available at the Aesthetic Realism Online Library