The Sculpture of Deborah Butterfield: A Thrilling Study of Strength and Grace

Butterfield, Deborah, Gallery Installation, LA Louver Gallery, Venice California

“Sculpture is trying to get to oneness through all kinds of variability, and trying at this time, to put together ugliness and beauty. … And earth, material, is used to show emotion and the meaning of the world.” — Eli Siegel

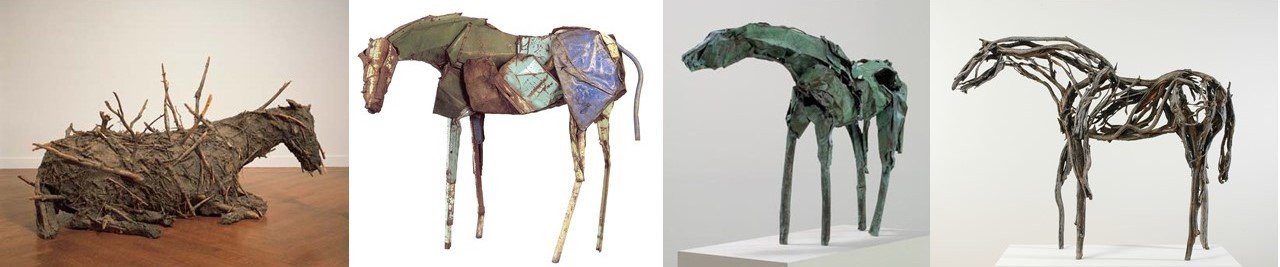

In his definitive 1950 lecture on sculpture, “Weight as Lightness: Aesthetic Realism Looks at Sculpture,” Eli Siegel the 20th century critic and educator who founded the philosophy Aesthetic Realism, explained: “Sculpture is trying to get to oneness through all kinds of variability, and trying at this time, to put together ugliness and beauty. … And earth, material, is used to show emotion and the meaning of the world.” The variability of earth and material, together with emotion and meaning is what we see in the work of the contemporary sculptor Deborah Butterfield. From inert matter—mud and sticks, salvaged steel, copper, dried wood cast into bronze—she creates life-size figures of horses that, in their physical stature, grace of form, nuance of gesture, convey qualities that are so alive.

The horse is one of the oldest subjects in the history of art, beginning in the caves of Lascaux 15,000 BC, to the American Wild West. The beauty of its form—that oneness of power and grace—has been immortalized in clay, marble, and bronze, and inspired artists such as Verrocchio, St. Gaudens, Degas.

Cave Painting, Chinese Horse, 15,000 BC, Lascaux Cave, France. Remington, Frederic, The Broncho Buster, 1895, revised 1909, cast by November 1910, Bronze, 2 1/4 x 27 1/4 x 15 inches, (81.9 x 69.2 x 38.1 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art Museum. Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius,161-180 D, Bronze, Musi Capitoli, Rome. Degas, Edgar, Horse with Head Lowered, ca. 1885 (cast executed 1919-1921), Bronze, 7 5/8 x 10 3/4 x 3 1/8 inches.

Deborah Butterfield has been described in Scholastic Arts Magazine as using “the form of the horse as a way of exploring the human experience.” I think a central aspect of that exploration is to see how we can make sense of ourselves as strong, forceful and also, hoping to be graceful in the minutes of our lives. The importance of Butterfield’s work is how strength and dignity are at one with gracefulness, even fragility, in a way that makes us have more respect for reality and more hope for ourselves.

The Power in Art is Also Delicate

Deborah Butterfield’s palette of material surprisingly consists of tons of metal scrap and dried wood sorted by color and spread over an acre at her Montana studio and ranch. From these she creates sculptures of horses that are delicate and strong in which she hopes to convey, as the review of her 2004 exhibition states “the very spirit of equine existence.”

Born in San Diego in 1949, she was affected by horses as a child. She now trains horses in the sport of dressage, known as horse ballet—in which horse and rider training together develop a communication so that the animal performs requested movements with a dignified and effortless grace. Horses, she said are “large and powerful, yet…gentle and interested in communicating.” And they are fragile. That “interest in communicating” is movingly expressed in Butterfield’s sculptures, as a delicate tilt or a subtle curve of steel conveys a shake of a head or flick of a tail.

“In order to be strong,” said Eli Siegel, “we have to be graceful and delicate.” Every person wants to feel powerful, in control and also feel at ease, and be kind. But if we exert strength without sensitivity, we are cruel, and grace without something vigorous, substantial, is awkward and frail.

Grace and strength working for the same purpose are present in the 1986 work titled Atiyah. Standing 6 feet in height, rods of rusty steel, bent and hammered into shape, define her form inside and out. How is it that this jumble of winding thin and thick steel bar and wire becomes the power and grace of “horse”? Surprisingly, lines of metal, with all their twists and turns are suggestive of internal organs and a delicate circulatory system. The thin legs are rigid, yet a slight curve in the back right leg seems to counter a shift of weight created as the head extends forward. Subtle undulations outline the neck and delicate rounded wire forms the mouth. The beauty of this work is in how Atiyah trembles between graceful gesture and chaotic tangle. She trustingly stretches forward as if to take a carrot from a hand. It is this sensitivity of gesture that makes for the life here—and “accurate sensitivity,” wrote Mr. Siegel, “is power.”

Butterfield, Deborah, Atiyah, 1986, Steel, 74 x 115 x 35 inches

What can the way power and delicacy or grace are together in this work teach us about ourselves? I know from my own life that women have used their delicacy politically—to have spurious power over a man; and women have also been forceful in a way that lacked kindness and true grace. Both of these ways—and I’ve had them— arise from a use of oneself to have contempt for the world. Art doesn’t make this mistake, because its purpose is to have respect for the world and how it’s made.

Two Ways of Going After Strength

Growing up in Springfield, Missouri, my parents and I lived in the beautiful region of the Ozarks. I loved its gentle rolling hills and how when cut through by a highway, you could see curves of green earth supported underneath by solid limestone. Like Deborah Butterfield, my father Don Ellison, loved horses from childhood, and with the help of my mother Beverly Burk, bred, trained and raced thoroughbreds. Daily I saw horses running and grazing in our pasture and was in awe watching my father befriend a new foal—gaining its trust with assuring tenderness and a strong, steady hand.

But I also wanted to have my way and when I didn’t get it would throw tantrums. I was competitive, feeling that horses, not me, were the center of my father’s life. I complained that friends went on vacations to ‘fun’ places like Disneyland, but we only went to racetracks—like Kentucky’s historic Churchill Downs. In an early Aesthetic Realism consultation after describing my father’s care for horses with some resentment, my consultants asked, “Why does he care for them so much? They explained that a horse “has tremendous strength and stamina to run as hard as they do and also have grace.” And they asked: “Have you granted yourself much sensitivity and awareness that you find inconceivable in your father?”

I had! It never occurred to me that my father, who I preferred to see as uncultured, was affected by beauty—the power and grace of reality itself, in the equine form; and that he was trying to make sense of these opposites in himself.

In college I began to study sculpture. I felt proud working in the studio carving and constructing with plaster and wood, sanding a surface or refining a contour to create a smooth and delicate form. But in daily life, I equated strength with my ability to be sarcastic and have a big effect on men. I saw no relation between my determination to get a man’s utter adoration, and the hollowness I increasingly felt. Though outwardly I tried to act graceful and confident, inwardly I felt unsure, and was scared I’d never have large feelings about a man.

Aesthetic Realism taught me that it was my own contempt that had me feel dull, inert and often mean. As I began to see that contempt made me weaker, not stronger, I began to have a different purpose with men. When I met Jaime Torres, who is a podiatrist and advocate for justice in health care, I was affected by the way he was strong and serious, yet had an easy manner and was a graceful dancer. And his criticisms of me, often humorous, have strengthened me and enabled me to be more sincere.

Art Has the Power We Want

Eli Siegel explained that “The ability to be affected by true power, is power. That is the thing that people have to realize—that to be unaffected by true power, is weakness.” Deborah Butterfield said her goal is “to gain insight by attempting to understand another creature.”

Butterfield, Deborah, Conure, 2007 welded found steel, 92 1/2 x 119 x 30 inches, (235 x 302.3 x 76.2 cm)

The 2007 work titled Conure, an assemblage of salvaged steel, is a beautiful drama of wreckage and nobility. At almost 8 feet in height, we are forced to look up and as we do, we see power at one with grace, even elegance. Every fragment is carefully placed. A blue diagonal beam denotes a proud neck, as its crest is defined by a delicate curving arc of thin steel. Its lowered head has a graceful humility. There is a slight turn to the head as if reacting to something we can’t see.

Grace is in the curving line—so true a horse’s physique—that begins at the head, rises and falls, up the crest, down the back, over the rump. This beautiful arabesque is at one with and supported by the force of diverging diagonal forms that create the neck, shoulder and body.

The legs of thin double bars of yellow steel bend subtly and curve, as if responding buoyantly to the weight they support. Yet they are fragile, thin, tentative, and we feel that all the parts will shift with the slightest movement. “Vulnerability and impermanence” said Deborah Butterfield “are a large part of the work” explaining that the legs are a “precarious moment on earth.”

Though the work is about horses, she’s stated that in many ways the work is “not about them at all” and that she was expressing her own feelings “in the shape of an animal”. We can ask: Is Deborah Butterfield dealing in her art with a question she has in life about strength and weakness, power and uncertainty? I think she is.

Butterfield, Deborah, Aspen, 2007, Cast Bronze, 89 x 87 x 60 inches