The Message of Pop Art: Everyday Objects Have Wonder!

Realism found new expression in the 1960’s with the advent of Pop Art. Artists such as Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Roy Lichtenstein, took popular images from advertising, newspapers, movies, as well as commonplace objects and saw them as worthy subjects of fine art.

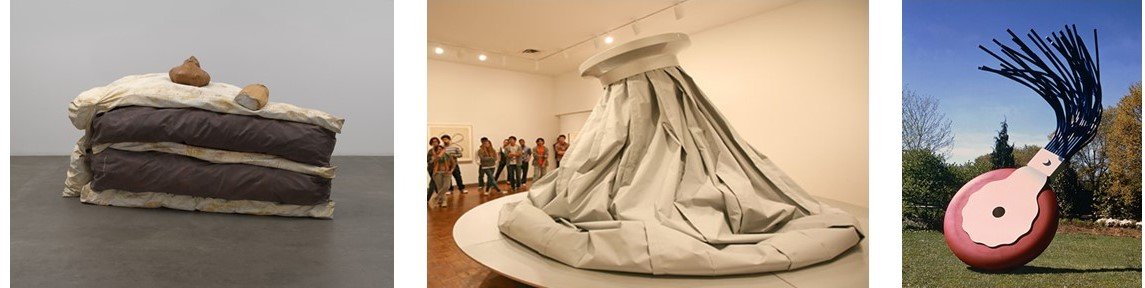

In the sculpture of Claes Oldenburg, monumental form is given to everyday objects that we can easily dismiss, even use without really “seeing” them—a light switch or spoon, for example.

The artist said he wanted people to recognize “the power of objects.”

Learning about the work of Claes Oldenburg made for a deep change in the students I taught at LaGuardia High School for Music & Art. I was fortunate to study and use the Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method and this landmark principle stated by Eli Siegel, the great 20th century educator and founder of Aesthetic Realism:

“All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”